To

orient ourselves, we enter slightly north of west. The plan reveals

exactly how the walls have been turned at right angles to the body of

the building. Their depth provided support for their height, with

each pier acting as a buttress. A pier is more than a column,

usually – in the simplest of words – not a circular or square

shape, but something more.

The

interior is taller than any church thus far described. The nave

rises to a height of 42.3 meters (138.78'). I believe this figure is

only exceeded by the Cathedral of Saint-Pierre in Beauvais,

which reaches a height of 48

meters (158'); see below. Robert

de Luzarches is credited with the nave design beginning in 1220, and

with the resultant visually dramatic effect based in great part on

height. Being taller than earlier churches, and keeping relatively

similar nave widths, the ratio of height to width of nave is

therefore greater here – a 3:1 proportion, contrasted to that of

Chartres at 2.6:1. Another element which adds to the extreme

vertical effect is the following: most French cathedrals from Notre

Dame onward, kept the height from above

the nave arcade to the ceiling vaults relatively constant, varying

from 18.3 to 19.8 meters (60' to 65').

What

changed,

as churches grew taller, was the height

of the nave floor arcade

– 9.8 meters (32') at Notre Dame, 14 meters (46') at Chartres,

15.9 meters (52') at Reims, and 19.8

meters (65')

here at Amiens.

What you are looking at are arches rising as high as a six story

building.

With

the height of the arcade alone equal to about a six story

building, and being almost half the entire nave height, the

impression is quite intense; ‘awesome’ is a popular but

appropriate word.

There

are 126 columns in this cathedral, most of them quite thin, very

skeletal, minimal in their diameters. All construction is

quite slender, and this, of course, adds to the almost surrealistic

nature of the design, to the mystical ecstasy evoked. Amiens is

often described as the climax of medieval sculptural architecture.

Luzarches is credited with a major innovation here in Amiens. His

column design evolved in three stages, as follows:

First,

the main ribs begin on the nave floor, and can be traced quite

clearly by the eye to the ceiling above, going over the vault, and

down the other side of the nave.

Second,

another set of ribs rises from the arcade capitals, and form the

diagonals crisscrossing the nave vaults, giving us

quadripartite vaults.

The

third set of ribs rises from the triforium level and frame the

gothic arches of the clerestory windows.

It

is all clarified in this view of the vaulting above the focal point

of the apse, the center semi-circle, in line with the nave. This is

a microcosm of the vaulting, in which every vertical goes up, over,

around, and down. Again, the structure is a visible skeleton of

stone members.

The

stained glass at this eastern most end of the church is dominated by

the color blue, which dominates to some extent the interior of Notre

Dame in Paris, and Marc Chagall's windows in St. Stephen's in Mainz.

Blue is a most spiritual color, especially when it is lit from

behind.

As

in many churches, there is a maze (in the fourth bay of the nave in

this church), created to serve as an initiation journey for the

faithful, who follow the black stripe for 234 feet (71.3 m.).

The

central slab contains drawings and names of the builders of the

church – something which contemporary building owners might note,

because more often than not there

is no indication anywhere of who designed a contemporary building.

Equally disturbing in much of the United States is that no one

working in a building knows the name of the Architect who designed

the building in which they earn their living!.

The

oak choir stalls date from the early 16th

century, 1508-1522 to be exact. There are 110

stalls built for the church canons.

Here,

detailed elements contain over 3,650 sculpted figures in 400 scenes

relating to biblical as well as secular activities. These latter are

of everyday life of Amiens at the time of their design; local

genre, in other

words. The scene on the right depicts a worker who carved a self

portrait hammering away. Craftsmen used to be proud of their

product.

History books have long referred to

the “Bible of Amiens” as something created in art form in

order to convey biblical tales to illiterate townsfolk. Personally,

my thoughts were always of words handed down by my Professors: the

stained glass windows. Further investigation has some texts

referring to these stalls as the bible. Comments have alluded

to the choir stalls – though these would have been

essentially out of bounds for normal citizenry.

A book review by John Gross, June 5,

1987 printed in the New York Times, had this to say:

Prefaces

to La Bible d'Amiens and Sesame et les Lys with Selections from the

Notes to the Translated Texts. By Marcel Proust. Translated and

Edited by Jean Autret, William Burford and Phillip J. Wolfe, with an

introduction by Richard Macksey. Illustrated. 173 pages. Yale

University Press.

“In

1885 John Ruskin, already deep in the last tragic phase of his

career, published The Bible of Amiens, an account of the

French cathedral, and more particularly of its West Porch, with

its intricate lacework of biblical figures carved in stone (emphasis

my own). He also singled out for praise, among the

cathedral's other splendors, the set of sculptures portraying the

story of St. Honore, ''little talked of now in the faubourg in Paris

that bears his name.”

Ruskin

also had this to say about the Gothic Architecture of Amiens:

"Gothic,

clear of Roman tradition and of Arabian taint, Gothic pure,

authoritative, unsurpassable, and unaccusable... not only the best,

but the very first thing done perfectly in its manner by northern

Christendom."

Certainly

we can add: “or by Western Architecture.” We shall see a

modern day transformation of the exterior statuary, which was

referred to by Ruskin, resurrected in brilliant color, through the

marvel of computerized projections.

A

rather graphic depiction of the beheading of John the Baptist,

located on the exterior of the north choir screen. Sculpted in 1531,

its special significance lies in the fact that the church professes

to have the actual head of John, which is produced every year on the

24th of June.

This

is the actual head, set on a silver tray. So many medieval churches

and their surrounding towns were financed by pilgrims, what today we

would call “tourists,” who came to venerate religious relics.

Their donations and business brought relative wealth to a community,

and the greater the attraction – religious-wise – the more

popular a venue became; here using the word “venue” based on its

Old French, “a coming,” from the Latin 'venire.'

The

“Weeping Angel” by Nicolas Blasset, sculpted in 1628, sits atop

the tomb of a church canon. It is very much in the manner of

Michelangelo's Medici Chapel tombs' sculptures, completed

a century before in 1524, in

that it dimensionalizes its composition, projecting into and out of

the frontal plane of the arch. The sculptor was sued by the family

of the canon, who were pleased with the work, but not the invoice.

The case was settled when Blasset added the angel to the composition

as a”gift” to the family, and the statue is possibly in tears

because of the legal action.

Now

to explore the Cathedral a bit further.

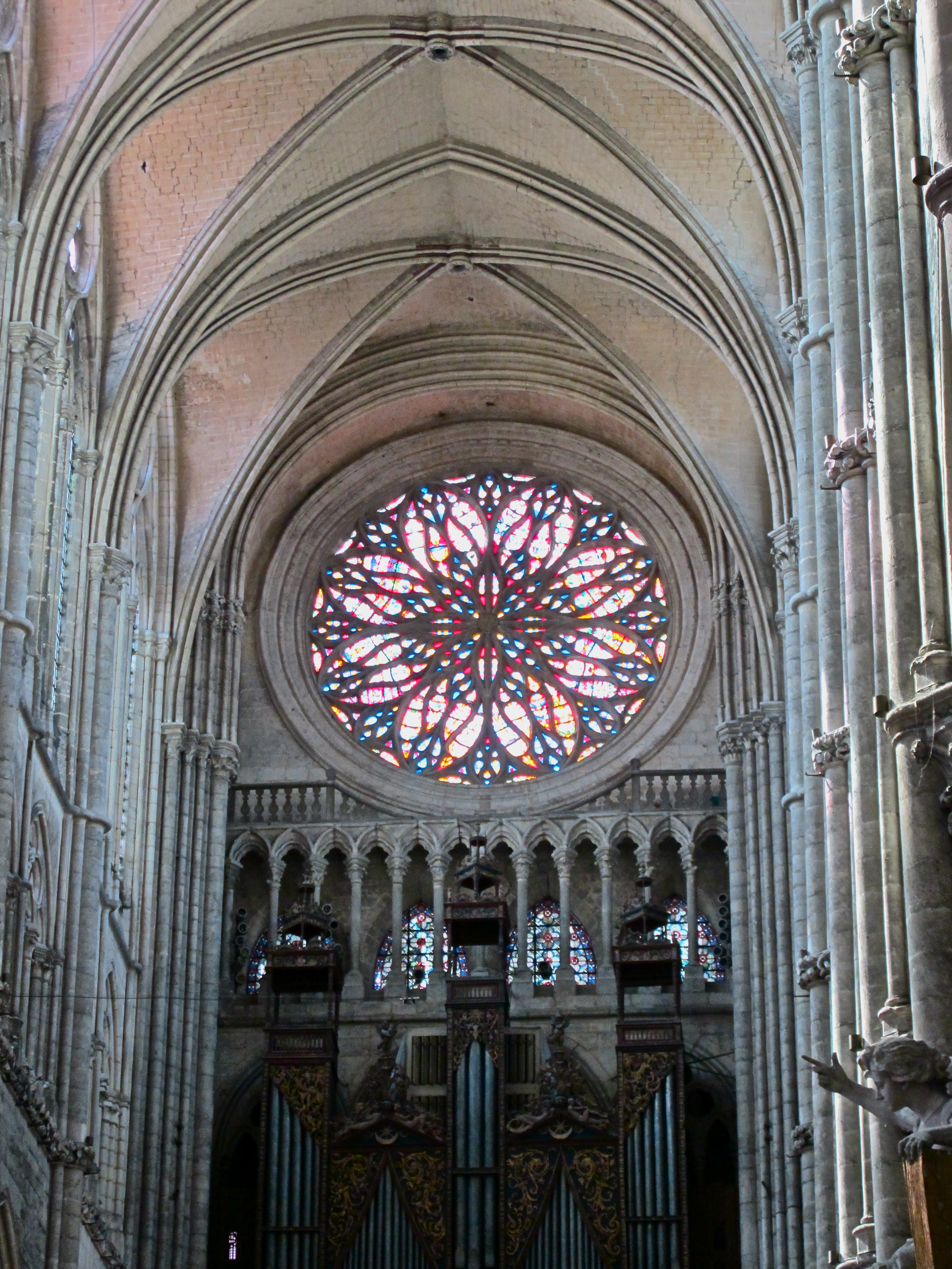

The

rose window of the western or entrance facade.

A

view into the southern side aisle, looking towards the transept. The

space is a church unto itself. Often wondering why so many churches

used black and white floor tiles in an alternating checkerboard or in

some pattern? One explanation of an unrelated floor was found in

reading Dan Brown's “The Lost Symbol,” in which he describes a

black and white floor as representing “the living and the dead....”

This could be applicable in a religious structure.

Looking

at the rose window in the South Transept. Every inch of wall surface

has been carved, etched, and detailed, or glazed. The intricacies

more than define the expression: “integration of art with

architecture.”

The

Baroque high altar was installed in 1751, and while beyond the scope

of Gothic development, it is, never-the-less, an integral part of the

church, and needs some small explanation. Designed by the Architect

Pierre-Joseph Christophle and sculpted by Jean-Baptist Dupuis, it

involves swirling clouds surrounded by a halo of light in shafts of

gold. Lots of symbolism, but at the same time, seriously criticized

by one author who claims it hides the chapels surrounding the apse

from view. Well, the first time I saw through into the apse from the

nave was in the cathedral of Granada, and it was , franly,

disconcerting. The chapels in the apse, or the chevet, are normally

approached by way of an ambulatory, continuing from a side aisle of

the main church. Those chapels are small, private, and customized

for individual worship. If anything, this particular altar piece

provides just such a necessary bit of privacy.

A

view of the construction immediately above the altar, so fundamental

in its structural honesty. Note the triforium gallery, and the

clerestory windows above. The continuity of all the elements is much

to be appreciated and admired.

A

detail of the triforium gallery, shown here in a bifurcation of a

bifurcated pattern (two main arches, each split into two

parts).

A

view towards the west, through the choir and its wrought iron screen,

and the main entrance situated beneath the organ.

The

intricately patterned floor, with perfectly inlaid marble.

As

we exit, the central portal, and its tympanum above, shown here to

illustrate the absolute lack of remaining color, but also to

illustrate the total integration of art and story-telling, with

architecture.