ABBEY

AUX HOMMES

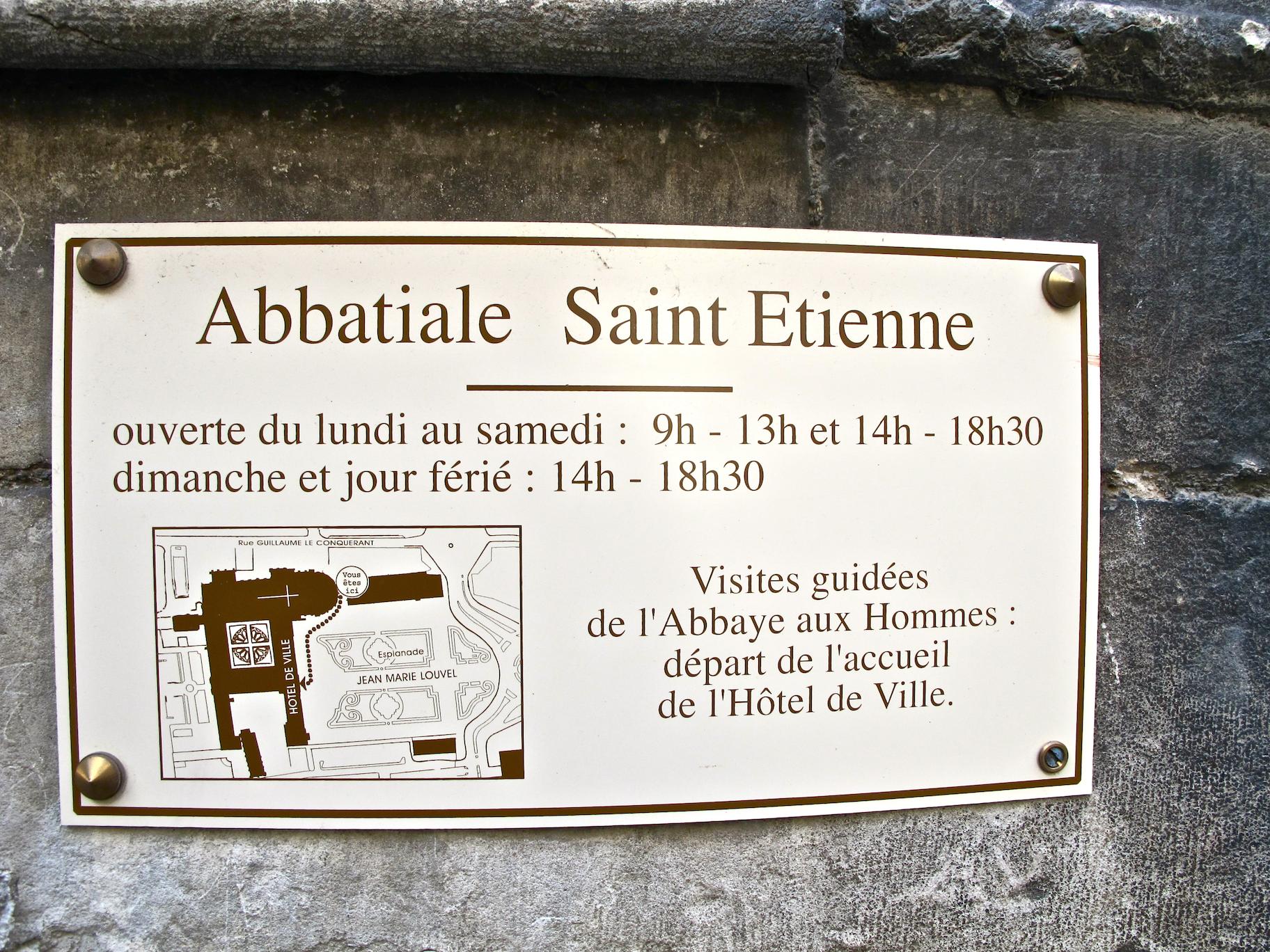

Also

known as "Sainte Etienne," the Abbaye-aux-Hommes, is a

French Romanesque church located in the west side of Caen,

a city in Normandy, located in northwestern France. To repeat,

sometimes the architecture in this region of France and in this time

frame (the 11th and early 12th century) is described as "Norman."

Interestingly, to add a bit to the information above, locals tell it

this way: Vikings were given land in this part of France in the year

911 in an effort to stem their periodic invasions into the rest of

what we call France.

The

"Northmann" brought with them an inspired sense of

construction, mostly in the development of monasteries and churches.

We could use some of that construction work ethic today!

Constructed

between 1068 and 1120, this particular church was founded by William,

Duke of Normandy. Remember this is the ruler who would eventually be

known as "William the Conqueror" because of his successful

invasion of England (see the Abbaye-aux-Dames, begun by Matilda, wife

of William, and also located in Caen - actually on the opposite or

northeast side of the city). Remember also, the two churches were

built to expiate or atone for the fact that William and Matilda were,

apparently, first cousins (some sources say “distant” cousins),

and their blood relationship was frowned upon, with regards to

marriage, by the church.

A

side note: William was buried in this church. At some point his body

was removed, then returned. But: William

the Conqueror's tomb was destroyed by Huguenots in 1562 during the

Wars of Religion - only a hipbone was recovered. Then the last of

William's dust was scattered in the French Revolution. Difficult to

say what exactly is buried inside this tomb.

This

is the west

facade

- the entrance

facade

of the church. This facade is one of the earliest to absolutely

define its interior layout by its external appearance. Remember the

three portals of Matilda's church. In width, we see a three-part

elevation, indicating the central or main aisle (the nave), as well

as the flanking or side

aisles

(also known as the ambulatories).

The

height of the western towers, combined with other verticals on the

building, began that reach towards the heavens that was to

characterize later Gothic church development.

The

octagonal spires at the very top of the twin towers were added in the

13th

century. There are a total of nine spires on this church, all

seemingly erected in the 13th

century. It is strange to say, but though this façade set the

design trend, almost as a prototype, it is one of very few churches

to have come down through time with its towers almost identical.

Very often local resources would be depleted prior to completion

of these massive edifices, and if towers and spires were ever

completed, they would be done in the style of the moment of the new

construction, therefore losing the original mirror image concept.

Frankly, these towers are magnificent, and not enough credit is given

this particular church for its “completeness.” Compare this

facade with that of 12th

century Notre-Dame la Grande in Poitiers (see “Poitiers” below).

Here

at Poitiers, Notre Dame la Grande – a preview – we see the three

part semi-circular facade indications of the interior, and also

spires placed atop the turrets of the corner buttressing towers.

These were added later than the original, but historians seem to

agree that the intent was to complete the vertical striving. But the

contrast with the images here in Caen is more than striking. This

particular church we are studying now, the Abbay aux Hommes, was –

well, to exaggerate, but to make a point - light years ahead of its

time, with minimal recognition of that accomplishment.

We

are doing this church backwards – beginning as we did with the tomb

of William, proceeding to the twin western towers. But in keeping

with out concept of “serial vision,” let us begin anew by showing

the very first glimpse of the church and its towers from la rue

Ecuyère, at a distance of about 0.3 miles (0.5 km). The spires

beckon.

At

Place L. Guilouard, we realize that we are approaching from the rear

or eastern end of the church, and that the Western towers are on the

far side of the church.

Standing

in the Esplanade Jean Marie Louvel, which is the main garden entrance

to the Hotel de Ville of Caen (the “City Hall”) we see the nine

towers cited above. And again, they are magnificent and

extraordinary. There are very few, if any, churches with such a

multitude of “fingers” stretching up to the heavens.

Flying

buttresses

are obvious on the exterior, helping to support the latest

construction of the church, that of the upper nave. That area was

completed in the 12th century. Earlier wooden roof construction over

the nave was removed in 1115, the upper section of the nave walls

raised to accommodate sexpartite

vaults, and at some point these flying buttresses were used to

pinpoint strategic support for that higher construction. As with so

much of Romanesque development, these buttresses would become a

feature of structural and aesthetic design of Gothic church

development.

The

western facade once again. The facade up to the spires is original

to the 11th century. The height necessitated buttressing,

and the four massive buttresses applied to the front elevation divide

the facade into the three parts representative of the interior, the

nave flanked by side aisles. The three sets of windows further

indicate interior arrangement, the nave floor, the triforium gallery,

and the clerestory. The south tower (on the right) is 262 feet

(80m.) high, while the north tower (on the left) measures 269 feet

(82m.) in height.

Typical

of Romanesque churches, the walls are heavy -7 feet thick (2.17m.) -

the openings small, created with semi-circular arches.

Remember that early church construction was conservative, walls

thick and massive, and obviously the larger the opening the greater

the danger of collapse. Until - by trial and error and greater

awareness of just what stone was capable of supporting - walls became

thinner, taller, and buttressed strategically.

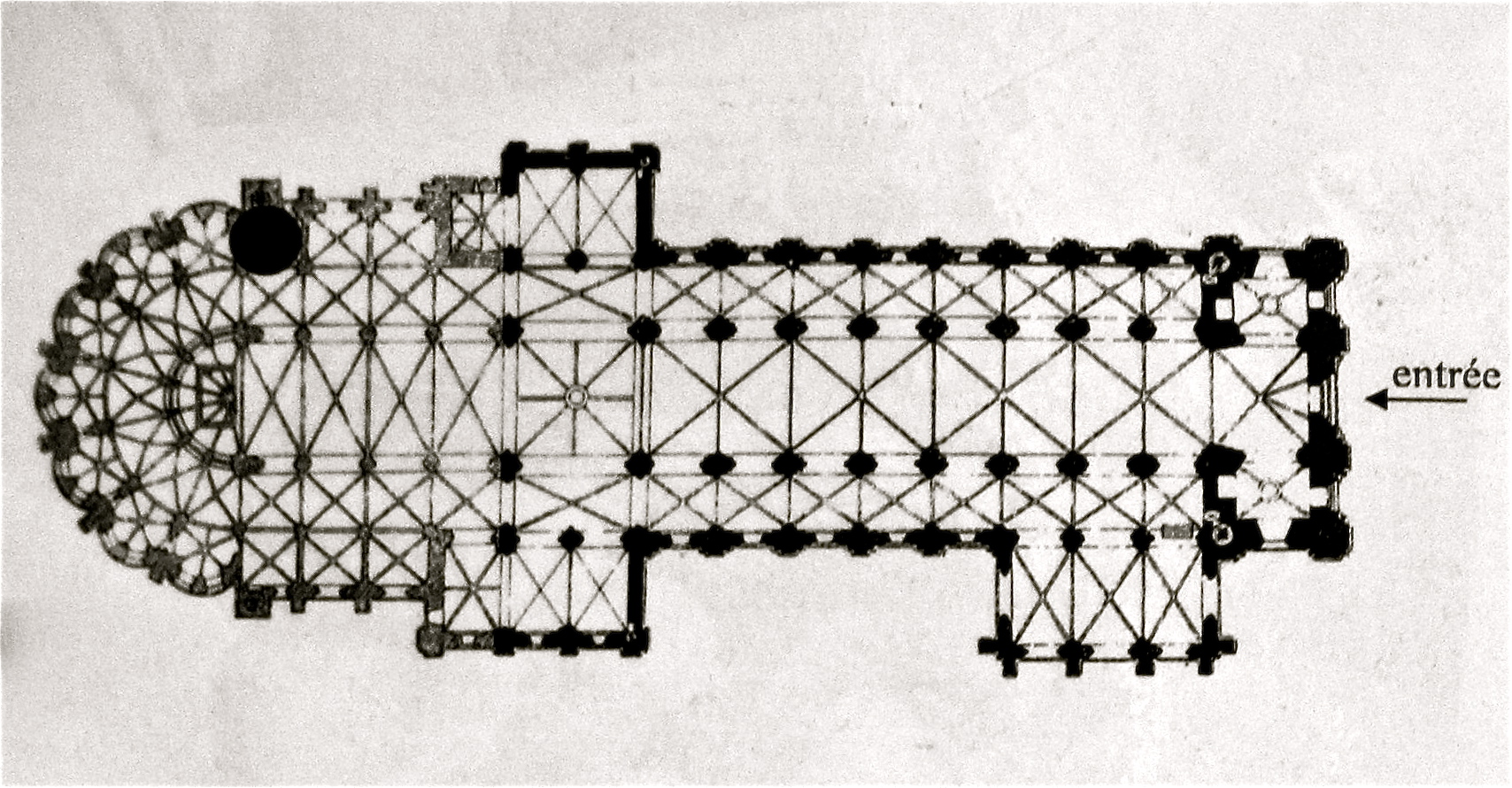

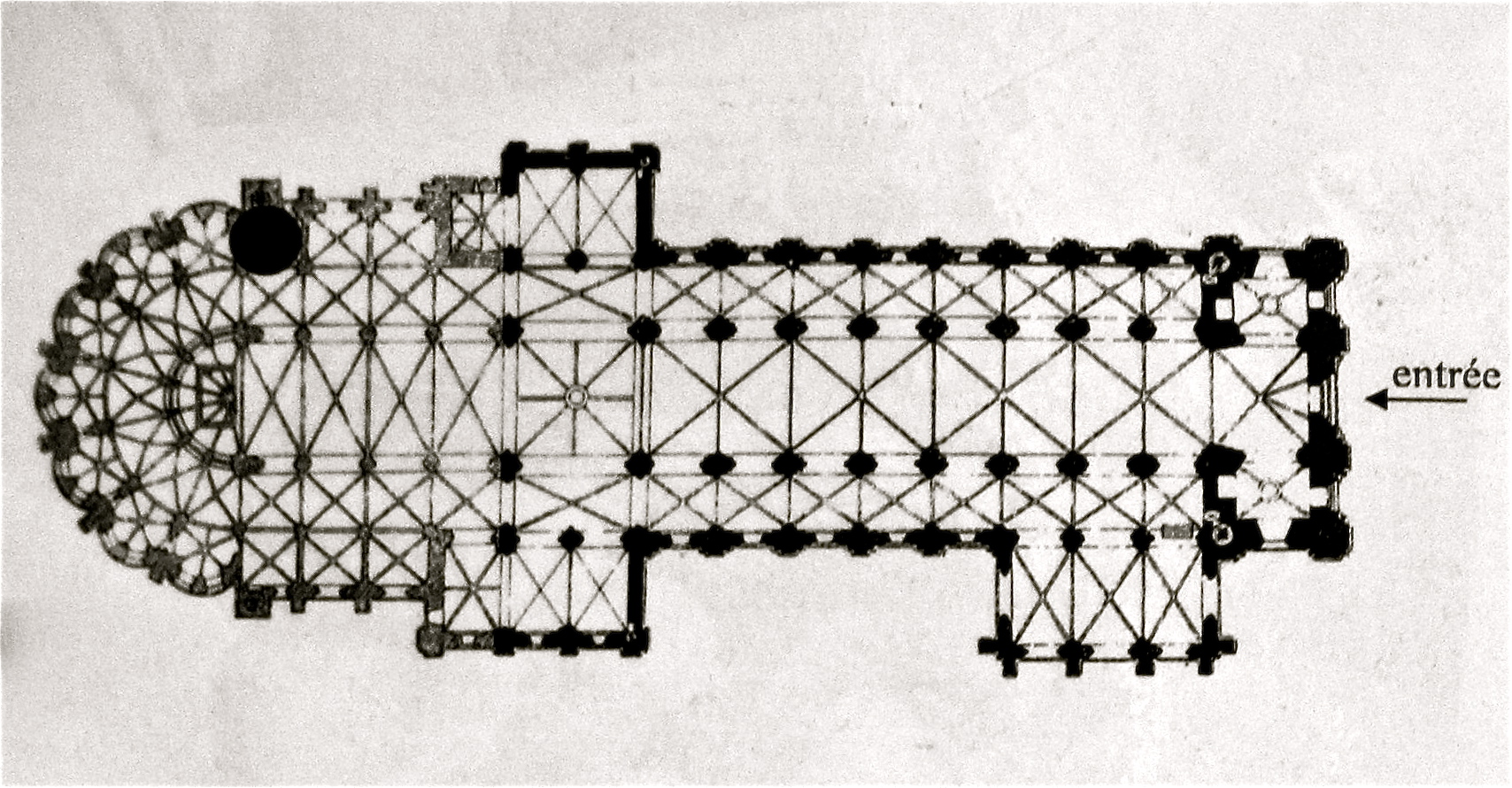

As

we enter, we shall review the plan of this church.

The

plan shows the overhead structural members – vertical and diagonal

lines. Note that immediately upon entering, the vaulting overhead at

each of the three entrance doors, is in four parts. Proceeding down

the nave, we see that there are six parts to each vault (the diagonal

and vertical lines which delineate a bay in the construction. The

crossing is divided into eight segments. The multi-angles of ribs in

the apse over the choir are part of a Gothic addition in the 13th

century. We shall explore all of these areas immediately. Note: the

black circle on the upper left indicates the area from which this

photo was taken, that of the Chapel of Saint Joan of Arc.

Internally,

just above the entrance, is the four-part vault, showing traces of

colorful decoration.

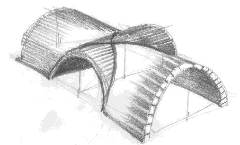

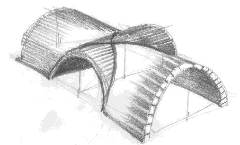

To

refresh a bit, the four-part groin vault, by the way, is known as a

"quadripartite"

vault, and seemingly resulted during Roman construction from the

intersection of two barrel vaults.

Here

we view the nave as it extends towards the altar. We are now dealing

with a feeling of procession, as mentioned above in the introduction

to the Romanesque. The semi-circular pilasters which have

transformed the piers into articulated verticals, traceable up to the

roof and over, forecasts the Gothic. The height is approximately 66

feet (20m.).

Sexpartite

vaults span the nave.

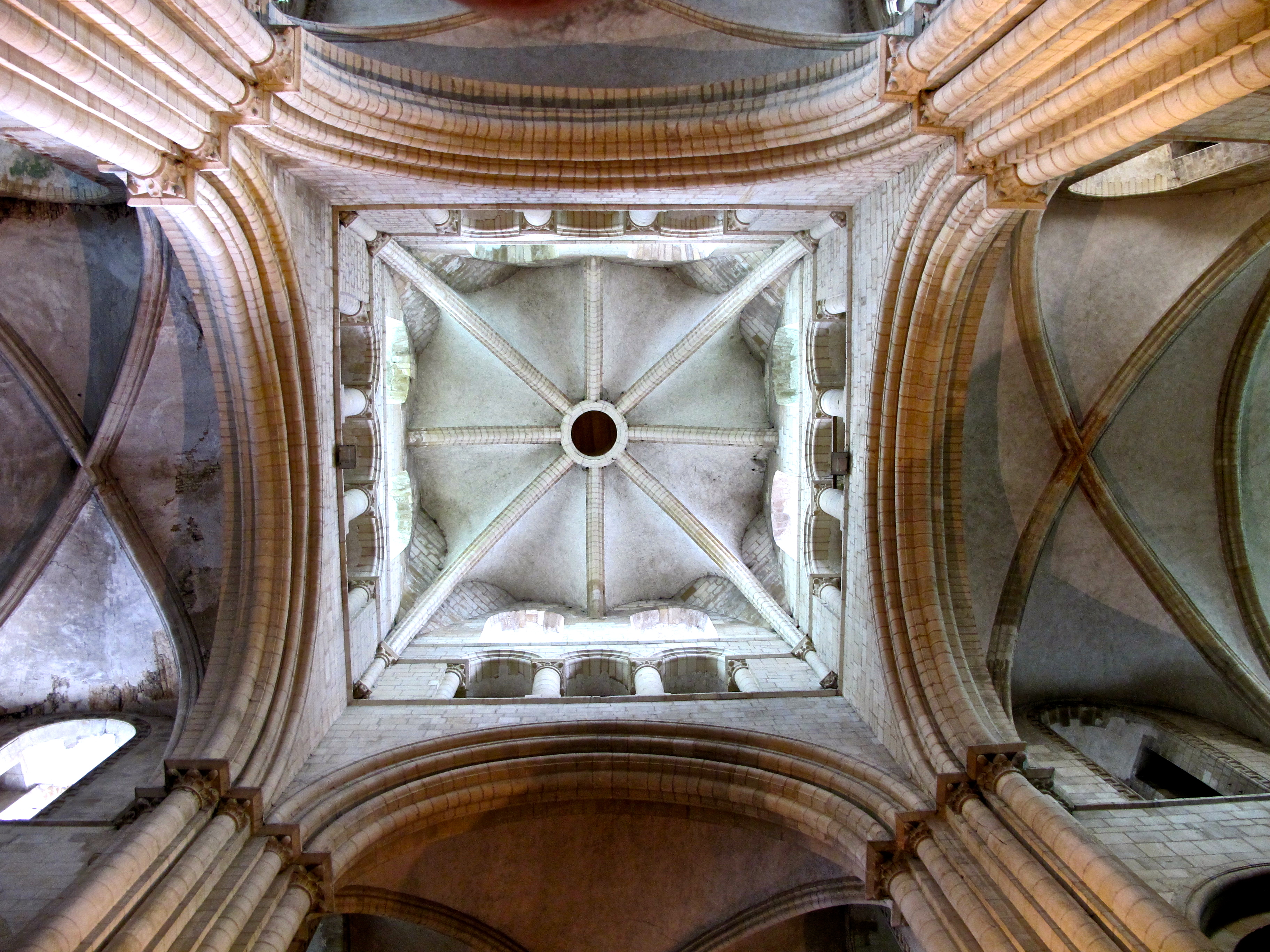

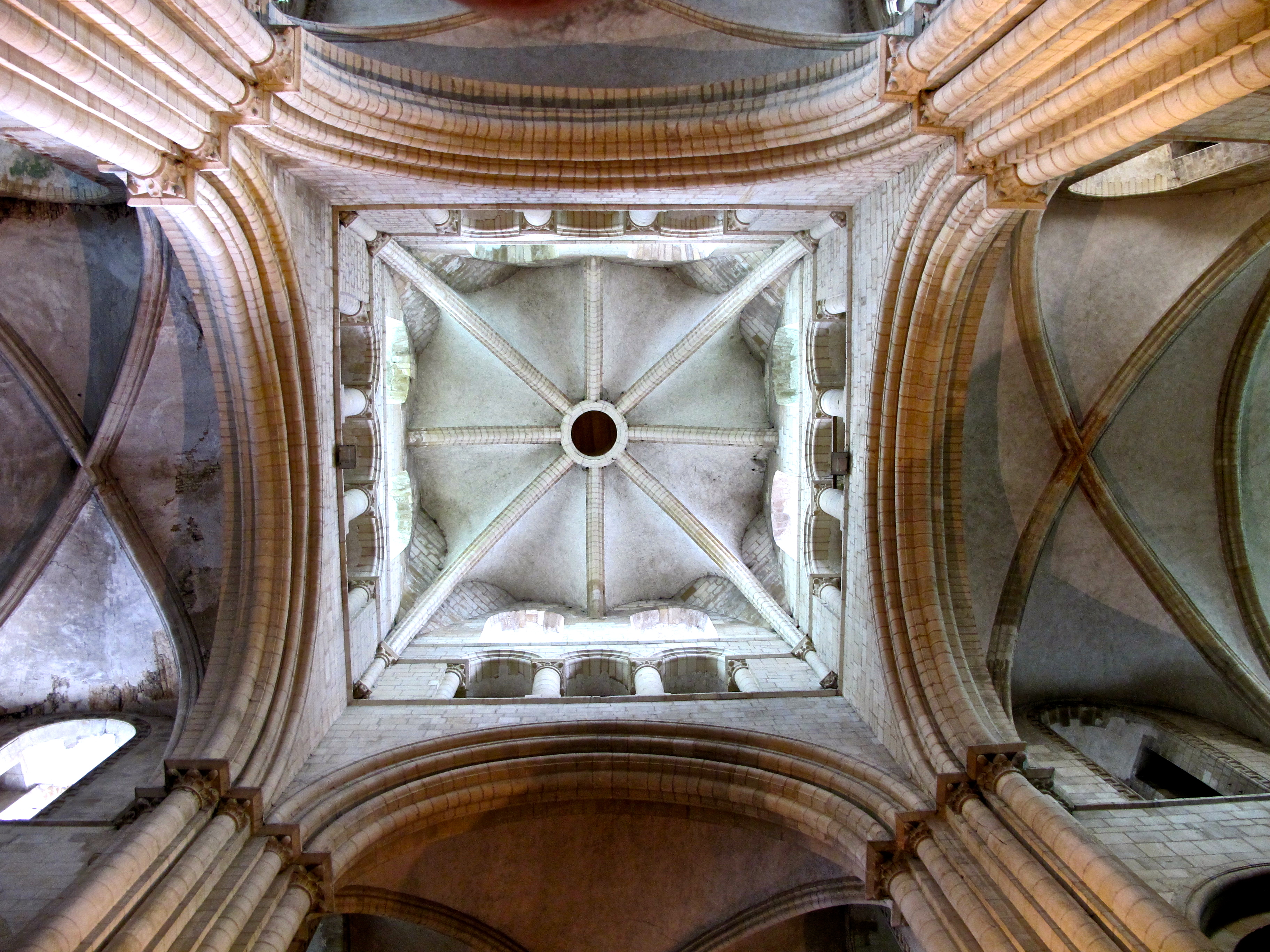

The

crossing dome, divided into eight segments. This is the intersection

of the nave and the transepts.

Its

height to the open circle, which incidentally as a continuous form,

takes all of the ribs pressing against it and carries their thrusts

around endlessly, measures 102 feet (31.2 m.) above the nave floor.

The highly articulated crossing construction is really rather unique

here. Most early churches merely placed groin vaults at the

intersection of the nave and transepts. This particular construction

is actually a tower, with clerestory windows, allowing not only a

sense of soaring height, but also a major source of light. Although

not directly related, this is really a highly innovative forerunner

of the principle of the Renaissance dome, placed over the crossing.

The

altar, with the apse behind.

The

apse, towering above the altar, dating from the 13th

century, when it replaced and expanded upon the original choir area,

is pure Gothic. The stone skeleton is the structure, pure and

simple. Materials have been minimalized, with just enough stone to

support itself. While the columns begin as round shafts, they do

articulate above their capitals, and can be traced up to a

convergence, from which some do come down on the opposite side.

While it remains for some later designs to become even thinner and

taller, allowing more light to enter, this never-the-less is a

magnificent accomplishment on the road through the Gothic.

There

are seven radiating chapels branching out of the apse. This photo

shows three.

This

is the chapel of St. Etienne (St. Stephen), the first Christian

martyr, for whom this church was named. Should you look up the bio,

you might find an English indie band, and a French football team, for

whom the band was named. Such is the stuff of which Wikipedia is

made. All of the chapels are similar, featuring altars lit by

beautiful stained glass, for which the French became famous. Notice

the pointed arches of those windows, a hallmark of the coming Gothic

development.

View

within the apse, behind the altar, an area surrounded by delicate

wrought ironwork. Contrast this work with Spanish and Italian

designs, which are usually heavier and simpler. An interesting

assignment would be to compare and contrast wrought iron works

throughout Europe, including England in particular. You might find

that each country has its own wrought iron identity.

Note

that most windows are semi-circular, in the Roman (or "Romanesque")

tradition, this typical in the ambulatory. Here, again, they often

refer to local architecture as "Norman" - be it Romanesque

in this case, or otherwise. Many of the nine spires were built in the

13th century, and because of that later development, it can be

assumed that the several pointed arches visible on the exterior

openings are from the Gothic period.

To

clarify: semi-circular arches following the Roman period are

described as Romanesque; pointed arches are indicative of the later

Gothic period. A

mixture within one building would indicate extended construction

periods.

One

other major innovation in the coming Gothic period - walls

began to be placed at right angles

to the building,

allowing so much more window space. Another way to look at that

development is to think of those right-angled walls as lateral

buttressing for the main body of the church. Or, as Louis I. Kahn

exclaimed when waxing poetic about Paestum "when the walls

parted, the columns became" (see Chapter THREE above). Some

writers have attributed that comment to Kahn's feelings about Gothic

development – well, it is applicable there, too. Now, obviously,

there had been columns before - look at Greek and Persian and

Egyptian architecture - but not in dimensions of over 100 feet in

height, which we shall see in the Gothic!

France

is noted for the stained

glass

within its churches. Aside from the aesthetic

beauty

achieved, and the spiritual

quality of the light produced

within the church, there was a practical purpose - the fact that many

church-goers were illiterate, and these windows provided pictorial

representations of biblical themes. The stained glass is so obviously

telling stories - almost always biblical in nature. But what we also

have is an artwork

integrated with the architecture.

The apse, where these windows are located, was lengthened about 23

meters (75') at a later date.

A

"checkerboard" floor pattern appears, as it does so often

in European church design. The origin or purpose of such design is

seemingly unknown. The simplest explanation would be that it was

created to relieve the monotony had the floor been all of one color

or of one material. But it is common in European design, be it

ancient or contemporary, that material and color vary, often

accompanied by a change in texture to add to the richness achieved.

Here

an application of gold to wrought iron. The French gild their

ironworks quite a bit, perhaps more so than Italians or Spaniards.

This

middle level is the triforium

gallery, shown

here in a very early form, but typical of what is to follow. It is

the floor of a gallery space – possibly used for overflow

congregations, or not accessible at all in many cases. You can see a

rib of a half-barrel vault, one of the earliest “flyng buttresses.”

Ribs

placed at column points articulate a half-barrel vault

quite obviously. This pinpoint support system focused structural

content specifically where needed. The ribs could concentrate energy

and reduce the rest of the vault to mere protective covering. It

would seem that this is one of the earliest uses of such an isolated

rib, in reality the forerunner of the flying buttress best known when

seen on the exterior, and as we saw in the opening frames. This

is another step in the direction towards articulated Gothic

structural development.

Note:

Some history texts attributed the earliest flying buttress to

structural supports within the triforium gallery at La Trinité

(Abbaye aux Dames). Subsequent site inspection seems to invalidate

such comments (see above in our discussion of the Abbaye aux Dames).

There might be isolated ribs at columns under the roof of the

triforium, but they are neither visible nor accessible, if they exist

at all. The actual isolated ribbed buttresses obviously appear here

in the Abbaye-aux-Hommes. As noted above in discussing the Abbaye

aux Dames, a planned visit to that church in the summer of 2011 might

shed some light on what has become a bit of a controversial subject

to this Professor..

As

with all Romanesque construction, arches are semi-circular, in the

Roman tradition, thus the name – we keep repeating it - Roman-like!

Reminder:

do see the Abbaye aux Dames for additional information.

To

clarify: semi-circular arches following the Roman period are

described as Romanesque; pointed arches are indicative of the later

Gothic period. A mixture within one building would indicate extended

construction periods.

One

other major innovation in the coming Gothic period - walls

began to be placed at right angles to the building,

allowing so much more window space. Another way to look at that

development is to think of those right-angled walls as lateral

buttressing for the main body of the church. Or, as Louis I. Kahn

exclaimed when waxing poetic about Paestum "when the walls

parted, the columns became" (see Chapter Three above). Some

writers have attributed that comment to Kahn's feelings about Gothic

development – well, it is applicable there, too. Now, obviously,

there had been columns before - look at Greek and Persian and

Egyptian architecture - but not in dimensions of over 100 feet in

height, which we shall see in the Gothic!

©

Architecture Past Present & Future - Edward D. Levinson, 2009