ROMANESQUE

DEVELOPMENT: VARIATIONS ON A ROMAN THEME

After

the Roman Empire began falling apart in the 5th

century, the Christian church spread Roman culture including, of

course, architecture. From this time to the time of Charlemagne

(Charles the Great), who tried to re-establish the original Roman

Empire, creating what he called "The

Holy Roman Empire,"

we have what should be called the early

Romanesque period.

Some historians call it the "pre"-Romanesque

period,

but that belies the fact that construction during all of this period

followed Roman architecture, thus: “Romanesque.” It couldn't be

"pre" or before

the manner of Rome because it was

the manner of Roman work. Here we will call it “early

Romanesque.”

There were early infusions of Byzantine design and structural

elements; we have already seen that. An intermediate period came

with Charlemagne during the 8th and 9th

centuries. Then authorities do agree on what we're going to call

"true"

Romanesque,

a time in which everything that had gone before coalesced into a new

variation on the earlier Roman themes. All of this was to lead, of

course, to Gothic

development. Everyone does agree that Romanesque means "in

the manner of the Roman."

Architectural

development that occurred with the advent of the officially

recognized Christian religion was given its form by several factors

which separated it from earlier Roman construction, yet was like the

Roman. We will discuss the following factors in this period:

1.

Lack of masonry skills

New

church rituals

Relics

leading to pilgrimages

Fire

But

first, a little summation to avoid confusion:

|

ROMAN

|

4thCentury

B.C.E.

|

to

|

4thCentury

C.E.

|

|

BYZANTINE

|

4th

Century C.E.

|

to

|

15th

Century

|

|

EARLY

ROMANESQUE

|

4th

Century C.E.

|

to

|

8th

Century

|

|

CAROLINGIAN

|

8th

Century

|

to

|

10th

Century

|

|

ROMANESQUE

|

11th

Century

|

to

|

12th

Century

|

|

GOTHIC

|

12th

Century

|

to

|

16th

Century

|

In

the beginning of Christian church development, existing Roman

structures,

basilicas,

were either used for expediency in providing places for worship, or

were copied

in plan, if not in structure. The atrium

(entrance

forecourt), narthex

(front

porch),

and nave

with ambulatories

(side

aisles – not evident in early designs, but prevalent as churches

grew in size),

all culminating in the apse

(semi-circular

end of the nave),

were standard. Transepts were added, often to accommodate additional

worshippers, or to provide smaller, more intimate chapel-like areas,

with their own entrances. Towers were erected to provide for bells,

often at the entrance, flanking the portals, but just as often over

the crossing.

The

major Roman basilicas, that of Maxentius and Constantine, for

example, and the Baths

of Caracalla

as another space maker, were built with groin

vaults.

As time passed, the skill

necessary to emulate those structures in large-scale building was

lost.

Roof

construction was again of wood, usually rafters / trusses. So for a

while, Roman vault construction faded from the scene, though the

plans continued. The illustration is the nave of the Cathedral of

Pisa.

Church

architecture developed new rituals

requiring new design elements. Monasteries

sprung up, and often priests wished to conduct their own mass, all at

the same time, so additional altars and their architectural places

were necessary. In this latter, transepts developed into their own

little churches, or chapels, often with apses at their ends (north

and south). At some point, apses were added along the side walls of

transepts, as well as in the original apse itself.

When

there was a grouping of apses within the original apse, that area

became known as a "chevet."

The

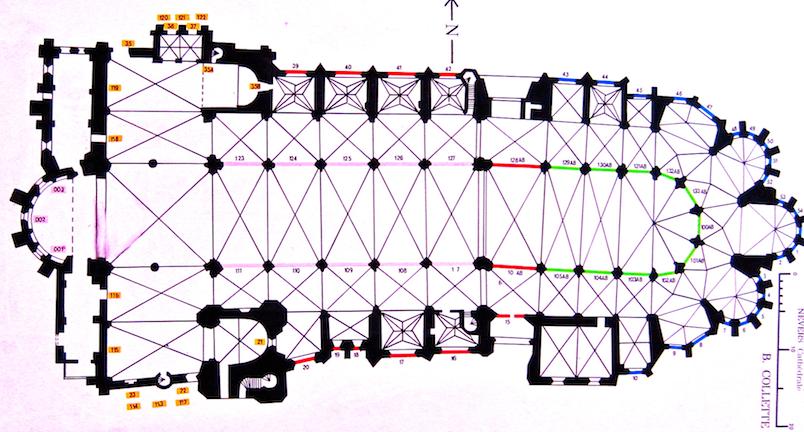

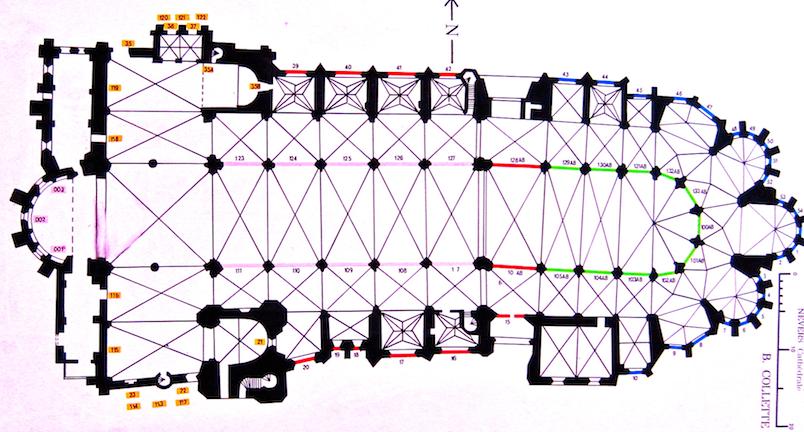

illustration above is a plan of the Cathedral of Nevers in France.

These

areas were usually dedicated to a particular saint, making each new

apse its own tiny chapel. This image is in the Cathedral of Autun,

France.

Choirs

began to develop, built right in the nave, at first defined by low

railings, then later with tall choir screens, as here in St.

Hilaire-Le-Grande, in Poitiers. These enclosed and separated the

choir from the rest of the nave, but usually designed so that vision

into and through them was possible. This allowed special services to

be held without disturbing the rest of the church, and vice versa,

yet was integrated within the whole of the church.

Typical

Choir stall, this located in Notre-Dame-La-Grande, also in Poitiers.

Relics

of religious significance came to be stored in churches. Often

miraculous attributes were applied to these relics, resulting in

their becoming a mecca for pilgrimages.

The following church, Notre-Dame du Puy, is located in Le

Puy-en-Velay in southern France. While it has been a pilgrimage stop

on the route to Santiago de Compostela, it has recently become a stop

in the Tour de France bicycle race.

The

cloister, shown above, is to the side of the cathedral, but is

indicative of what an atrium/forecourt would have looked like. This

cloister dates from the 11th

to the 12th

century, and features a protective arcade. The church owes its spot

on a pilgrimage route to miraculous healings attributed to a

visitation on its site by the Virgin Mary in the early years of

Christianity. The church itself was begun in 430 C.E.

Of

special interest is a statue known as “The Black Virgin.” Made

of Cedar, its exact origins are unknown, except that it was created

in the 17th

century, and replaced a previous figure burned in 1794, during the

French Revolution. Rebellions and revolutions usually go after

figures of authority in their quest to “change” things, and

religious symbols have always been targets, dating back to

decapitation of Roman sculptures deemed “pagan” by religious

zealots. As I write this, the assault on God and religious symbolism

is rather rampant in this country.

Routes

for pilgrimages were developed, with pilgrims making a circuit often

from one country to another. Large numbers of pilgrims entering a

church at the same time began to disturb the normal services being

held. This resulted in the designing of the side aisles to wrap

around the main apse, allowing visitors to circumnavigate the church

without interfering with its regular activities. Sometimes the apses

in the chevet would contain relics.

Considerable

movement

developed within these religious structures, at complete variance

with the classical forms developed by the Greeks, then the Romans, in

which few were admitted, and movement was static. Suddenly, there

was axial

movement,

from narthex to apse, be it in the nave itself or through the

ambulatory side aisles. The long,

relatively narrow nave required minimal spanning. Rows of columns on

either side allowed beams or trusses to cross, while the columns

themselves created a staccato rhythm of verticals leading the eye

from narthex to apse. Whether they were colonnades or arcades, the

naves moved you visually. Little

engineering knowledge or serious stone cutting was required.

Additionally,

processions

beginning at the altar came down into the nave itself. You could

almost think that this beginning sense of movement, this axial

progression,

would lead to the Baroque civic designs of the 17th

and 18th

centuries, beginning in Rome itself, and spreading throughout the

European continent. Unfortunately, the world would have to wait

almost 1,000 years.

Another

factor in the development of this Romanesque architecture was fire.

The

retrogression to wooden roof construction attracted lightning.

At first some churches burned and were subsequently rebuilt.

However, things got serious when relics began to be stored in

churches and were then lost in the fires. While

the churches could be restored,

the

relics could not be replaced.

In

response

to

the need to

cut the threat of fire,

stone

came back

as a construction

material. Masons developed who could learn the craft once more.

Small stones made up what once had been monolithic structural

elements. One step, one stone at a time. The

wooden roofs were replaced with stone vaults.

At

first, the vaults were simple barrel

types. The major problem posed was the

inability to pierce the continuous structure with openings for

windows,

for light.

Scaffolding

was the next problem. These barrel vaults required continuous

scaffolding, or centering,

during their construction. What seemed like a forest of trees would

be involved in constructing the barrel vaults. Viewed above is the

nave of Notre Dame du Port in Clermont Ferrand.

At

some point, separations

were made in the nave

- at the columns, creating

a beginning

and an end

to each segment of the vault, allowing centering to be used, the

vault completed, then

the centering was reused in the next segment.

The barrel vault did take the eye straight down to the apse, but

light remained the biggest problem - or actually the lack

of light.

Image taken in Nevers.

Here

at Nevers domes were used at the crossing and over the altar.

Elsewhere domes were the main structure in procession down the nave,

but created pockets of space, which interrupted the visual flow. That

effect is visible here at Nevers, showing the crossing and the apse.

At

yet another stage of development, someone reinvented the groin vault,

or at least at first the simple intersection of barrel vaults. An

early groin vault is this one in Notre Dame du Port in Clermont

Ferrand, also in the south of France. Eventually crossing of the

nave vault with vaults turned at ninety degree allowed light to enter

those sides. Supports developed into what would be called "bays,"

and a differentiation developed between the main, large bays of the

nave, and adjacent smaller bays of the side aisles.

To

support the heavy stone vaults, as contrasted to the lighter wooden

roofs, architects used massively

thick exterior walls,

and heavy

internal piers.

This masonry vaulting replaced the highly flammable wooden roofs of

early Romanesque structures.

As

discussed in the section on St. Apollinare in Classe, and developed

at St. Paul's Outside the Walls, the nave was taller than the side

aisles, allowing clerestory lighting.

This

is well expressed in St. Denis, just outside of Paris.

All

arcades, barrel vaults, and groin vaults employed semi-circular forms

in the Romanesque period. When

you see a pointed arch,

you

will be looking at something "gothic,"

a new

development.

©

Architecture Past Present & Future - Edward D. Levinson, 2009